Up my left arm runs a winding, jagged scar that makes “shark attack” a believable explanation.

It’s 130 stitches and hours of surgery’s worth of curiosity.

And “shark attack” has, in fact, been the story told to countless wide-eyed children.

For pretty girls (pre-marriage), it was the aftermath of a fight with a guy this big.

For those close enough to know about my lifelong mental health struggles - which, Welcome!, now includes you - it sometimes prompts a sobering, gently prying, “Hey, did you…?”

That question never seems to have a second half.

The real story is none of those things.

It is neither exciting, sexy, nor grim.

It’s complicated and medical and includes the phrase “as the door slammed shut,” which - story-wise - is not awesome.

Somewhere along the way, though, I realized the truth wasn’t the point.

The point was the scar existed, and people wanted to know what it meant.

That’s what scars do. They invite interpretation. They beg for meaning.

And the older I get, the more I believe: that meaning isn’t fixed.

It’s something you choose. Something you shape.

You decide what your scars are allowed to say.

And so, today we meet Bethany Hamilton.

Like all of us, she didn’t get to pick her scar.

But like all of us, she did get to decide what it says.

In your corner,

THE LEGEND

Before dawn on October 31, 2003, thirteen-year-old Bethany Hamilton paddled into the crystalline waters of Tunnels Beach on Kauai’s North Shore.

A local prodigy in Hawaii’s fiercely competitive surf scene, Bethany was chasing waves, yes - but she was also building a future.

Born into a family that revered the ocean, she understood its rhythms. To her, it wasn’t just a playground. It was something closer to inheritance.

Maybe even identity.

In Hawaiian culture, the ocean is sacred - a source of life, and also a force to be feared.

Bethany moved through it with reverence on the outside, and fearlessness on the inside.

That morning, floating beside her best friend Alana Blanchard, her arm lazily draped in the water, she was exactly where she felt most at home.

Until the ocean reminded her whose home it really was.

THE MOMENT

It happened without warning. No music, no buildup. Just a 14-foot tiger shark rising from the deep and, in a single bite, severing Bethany’s left arm below the shoulder.

The water bloomed red.

Time stretched and collapsed all at once. Panic never came. Instead, Bethany turned and started paddling. It’s not instinct so much as second nature. A knowing. Years of muscle memory kicked in, and she made her way back toward shore.

Holt Blanchard, Alana’s father, tied a surfboard leash into a tourniquet. It likely saved her life. By the time they reached land, Bethany had lost more than half her blood—but she never passed out.

This was not the ocean being malicious. It was being wild. And Bethany Hamilton had become part of its story.

THE WORDS

“Did that really happen?”

That was her first thought. Again, not panic. Not even pain. Just disbelief. The mind trying to catch up with the body.

The words that would follow her for years came later, when reporters and strangers and thousands of kids asked how she kept going:

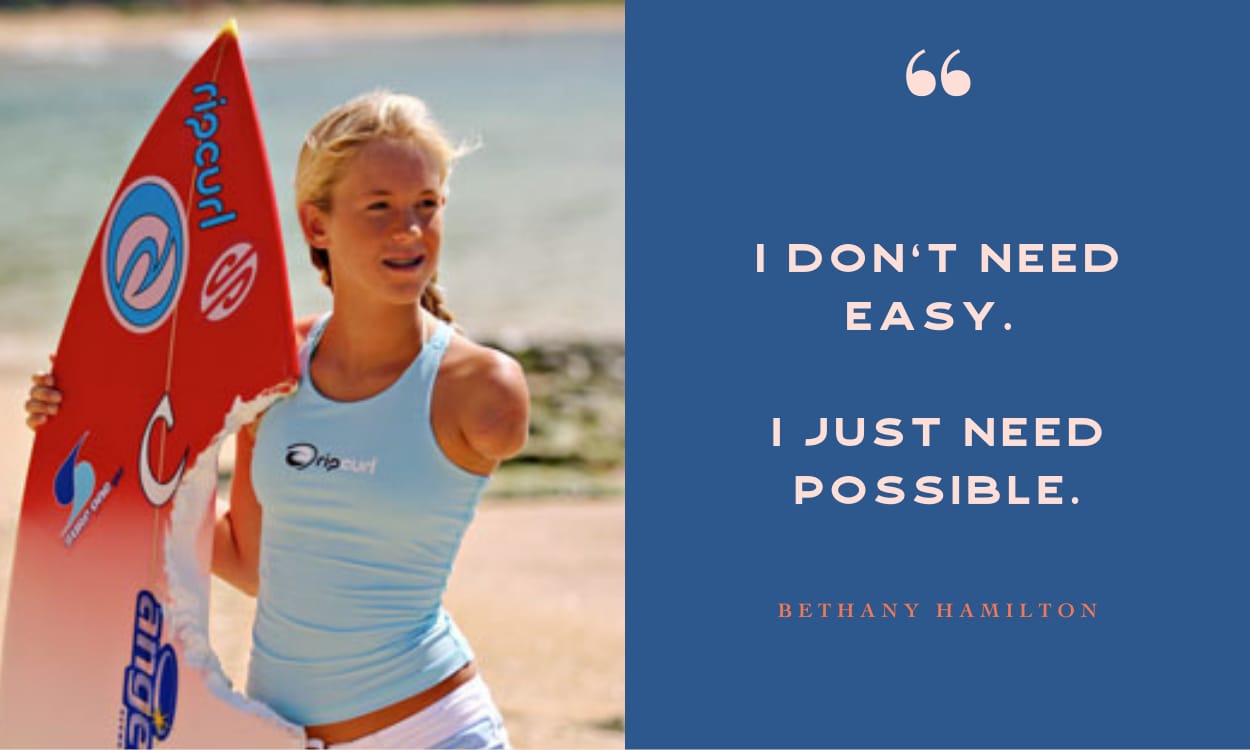

“I don’t need easy. I just need possible.”

When she was asked about getting back on a board just 26 days after the attack, she didn’t give a soundbite. She gave a decision:

“I could either just give up and not do what I wanted to do with my life, or I could get back out there.”

She’s been honest, too, about the parts that didn’t fit cleanly into a comeback narrative:

“People see the comeback. They don’t see the mornings I would look in the mirror and cry. They don’t see the times I’d get frustrated trying to do simple things and throw whatever I was holding across the room.”

Bethany has always told the whole story - pain and possibility, grit and grief, the fall and the fight to stand back up.

THE TRUTH

To use “improbability” is to completely undersell the absurdity of Bethany’s return. It was, neurologically speaking, almost impossible.

There’s a term for what happened to her: post-traumatic growth. It’s what psychologists use to describe people who don’t just recover from trauma, but somehow come back changed. Expanded. Adapted.

The science says the brain begins building new pathways. That purpose helps. That movement helps. But most people take months, even years, to find their footing again.

Again, Bethany got back on a board in twenty-six days.

She had to relearn everything. New balance. New paddling. New center of gravity. Her surfboard became a prototype. Her body became a lab. She trained her right arm to do the work of two. She changed how she stood. How she moved.

Resilience, in her case, wasn’t about getting back to normal.

It was about building something new from scratch.

THE ECHO

In hindsight, the return to surfing might have been the least remarkable part.

She founded a nonprofit for amputees. She authored books. She started a family. She became a mother of three.

And - maybe most remarkably - she became an advocate for shark conservation.

That’s the part that’s easiest to miss.

She didn’t just forgive the ocean. She tried to understand it. She didn’t make her scar a spectacle. She made it a platform. And she didn’t just regain control of her body so she could return to its greatest joy.

She stitched deep, deliberate meaning from it all. At the exact place she’d been pulled apart.

THE LESSON

We don’t get to pick our wounds. But we do get to decide what to make of them.

Was it a shark attack? A bar fight? A moment you don’t talk about anymore because talking about it never helped?

The story you tell with your scars doesn’t have to be noble. It just has to be yours.

Bethany went back in the water. That was her decision. And she turned something painful into something useful. Not everyone does. Not everyone has to.

Maybe you’re still on the shore, wondering if it’s even worth trying again. Maybe you don’t want to write anything yet.

That’s fine. That’s okay.

What matters is this: Your scars are yours.

And so is the story they get to tell.

Remember That Scene In…

Christoper Nolan’s The Dark Knight?

When Joker tells the story of how got his scars?

He says it was his dad. Then his wife. Then something else entirely.

It’s not contradiction - it’s choreography. He’s not trying to be understood. He’s trying to control the room. Each version keeps you off balance, which is exactly the point.

That instinct - rewriting, reframing, dodging - isn’t unique to villains. It’s human. We all revise the story when the truth feels too sharp to hand over raw. We smooth it out. We make it digestible. We turn it into something people won’t flinch at.

Eventually, though, if we’re lucky, we realize we can write a new version. Not cleaner. Not prettier. Just more honest.

There’s a concept in psychology called story editing, developed by Timothy Wilson. It’s built on the idea that people are natural storytellers - that we make sense of our lives through the stories we tell about what’s happened to us. These stories don’t just describe who we are. They shape who we become.

Story editing isn’t therapy. It’s not performance. It’s the process of going back to a hard thing and asking, “Is this still the story I want to carry?” It’s not about rewriting facts. It’s about revising meaning.

And that meaning matters - because the stories we tell ourselves guide how we live. They determine what we believe we deserve. What we think we can survive. What we give ourselves permission to begin again.

Most of the time, the first story we tell about pain is the one that helped us endure it. But endurance isn’t the same as clarity. And it’s rarely the same as peace.

Story editing offers a way forward. Not by erasing what happened. But by giving you the pen.

What comes next doesn’t have to match the beginning.

It just has to be true.

For Lee Corso

Before four decades (!!) redefining college football fandom.