The most meaningful endings rarely announce themselves.

I’ve carried a few that still feel vivid - not because they were dramatic, but because I knew they were final while they were happening.

The morning after high school graduation, I stood at the edge of the neighborhood pool while my classmates laughed and splashed in the water. I didn’t join them. I just watched, knowing I was taking in the closing chapter of my suburban childhood. Then I walked home alone.

Years later, my father and I spent one last night in the house I grew up in. It was already empty, our voices echoing off bare walls. We sat on the floor and watched TV. I don’t remember what we watched - just that it was the last time.

Those moments are rare. Usually, we don’t get the courtesy of a clean goodbye.

Most endings arrive quietly. No curtain drop. No final line of dialogue. Just the slow dissolution of something that once felt permanent.

We don’t get to play Pam and Jim, saying “click” so the best parts of our lives end up preserved in the photo album of memory.

And maybe that’s okay.

Maybe part of growing is learning to hold gratitude not just for the moments we knew were sacred - but also for the ones that slipped by without warning. The almosts. The never-agains. The things that were perfect while they lasted, even if they didn’t last long.

That’s the paradox of impermanent perfection: the things we can’t keep are often the ones that shape us most.

And if we're lucky, we learn to say thank you - even when we don't get to say goodbye.

In your corner,

THE LEGEND

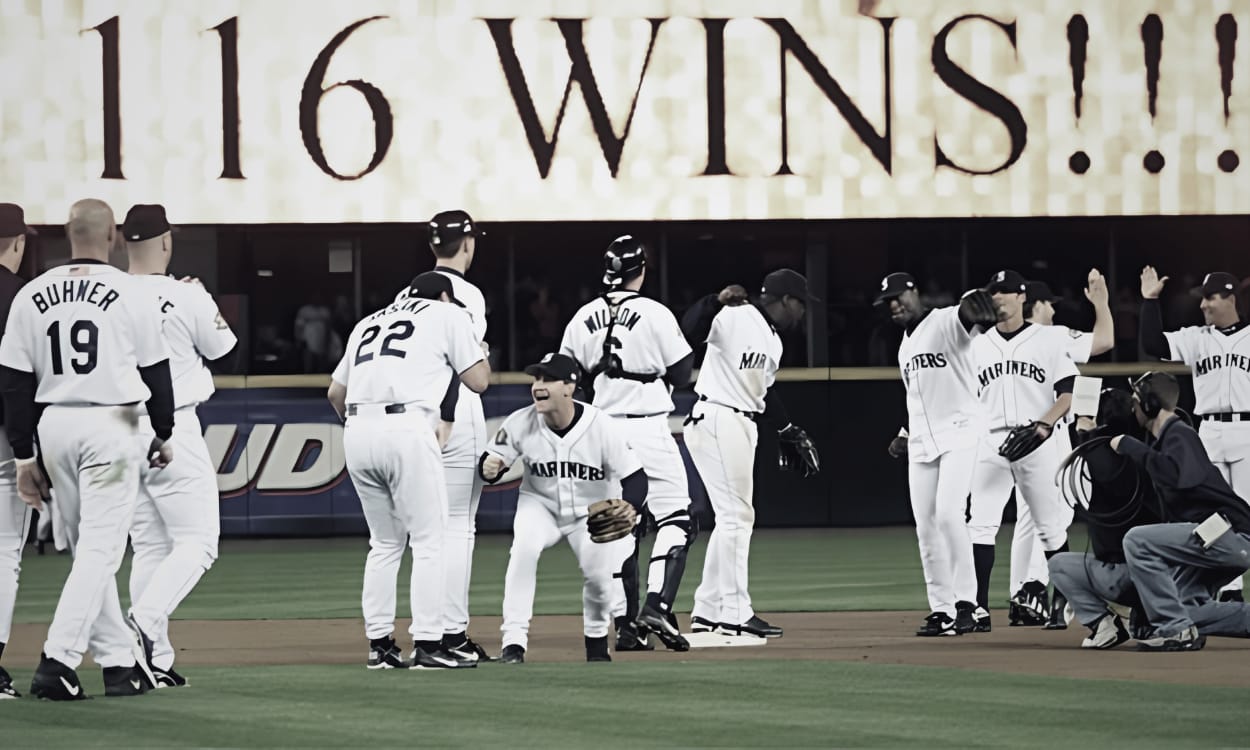

In baseball’s long memory, certain numbers become monuments: 755, 56, .406.

But 116 stands apart - both a pinnacle and a paradox, a symbol of perfection and its painful absence.

The 2001 Seattle Mariners built their statistical cathedral in the wake of loss. After Alex Rodriguez left for Texas’s riches, they were expected to crumble.

Instead, they became something greater: a team without established superstars but with unmatched cohesion. They won 116 games - more than any team in the modern era - yet their October ended in silence.

Their brilliance remains suspended in baseball’s consciousness: an impossible summer, forever shadowed by an unfinished autumn.

THE MOMENT

October 22, 2001. Yankee Stadium. Game 5 of the ALCS.

Seattle had spent all year outrunning doubt. But in the ninth inning of an elimination game, there was nowhere left to run.

The Yankees led 12–3. The outcome had been decided long before the final out, but that didn’t make it less brutal.

The air was heavy with October chill and Yankee inevitability - the kind of atmosphere where visiting dreams had died three Octobers running.

The Mariners dugout was still. Players sat motionless, their faces frozen in resignation.

Mike Cameron stepped in and slapped the first pitch to right.

Shane Spencer dove.

Final out.

Seattle stared out as the Yankees dogpiled. Lou Piniella stood at the rail, jaw clenched, as Yankee Stadium roared.

Some losses arrive like heartbreak.

Some arrive like inevitability.

This was both.

THE WORDS

"The amazing thing about baseball," Lou Piniella once said, "is that no matter how many games you win, unless you win a World Series, you're going to feel disappointment."

That’s the paradox the 2001 Mariners walked into.

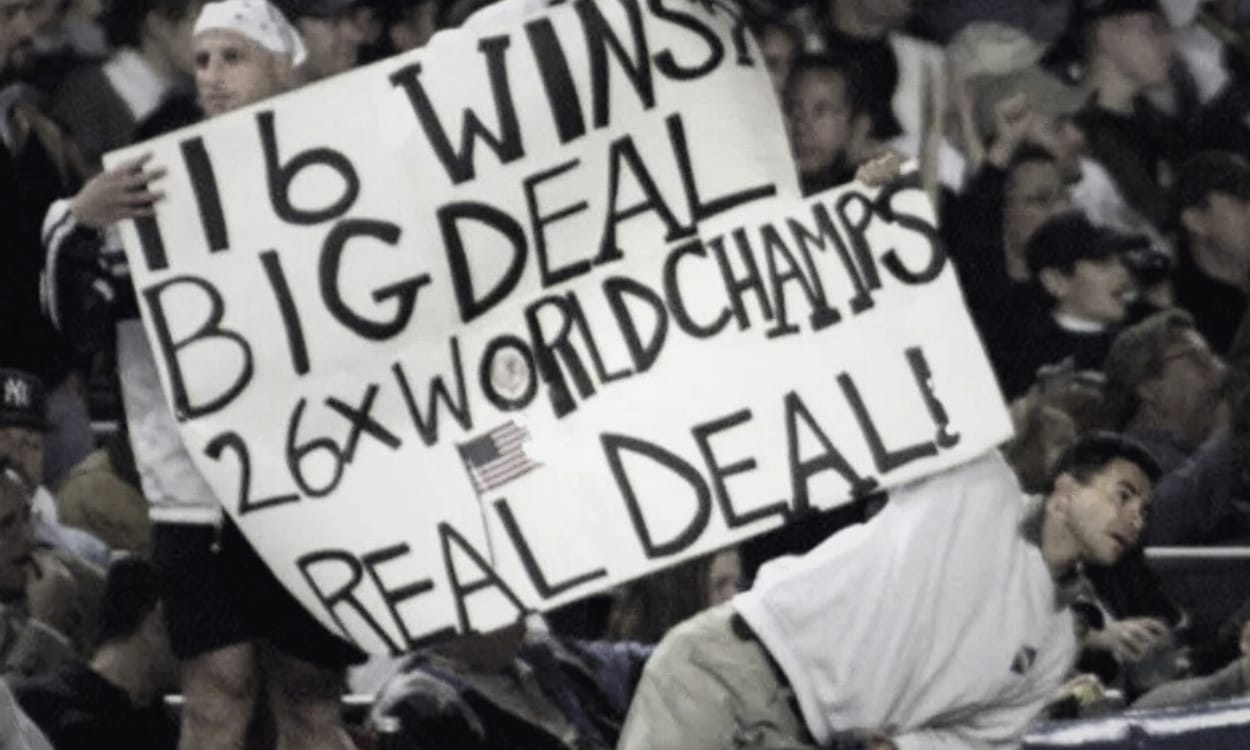

One hundred sixteen wins - a mountain of achievement - reduced to kindling in five October games.

The team that never lost two in a row all season dropped four of five when it mattered most.

Still, for the players who lived it, that year remains unmatched.

“We had a special group,” Bret Boone said. “Every night, we felt like we were going to win.”

No panic. No drama. Just a perfect summer.

But after summer comes fall.

THE TRUTH

Baseball is two sports: the marathon and the sprint. The regular season rewards consistency; the postseason demands brilliance in moments. The 2001 Mariners mastered only the first.

Their greatness was democratic - a selfless superstar new to America, a relentless lineup, a deep rotation, a lights-out bullpen. They outscored opponents by 300 runs, dismantling teams with ease.

But in October, dominance isn’t enough. It must be punctuated by moments. The Yankees had those: power pitching, timely hitting, October resilience.

And then there was the context - baseball played in the shadow of September 11. The Mariners were a marvel, but the Yankees were a symbol. An emotional inevitability.

Perhaps Seattle’s beautiful summer never stood a chance against a story already being written.

THE ECHO

The 2001 Mariners hover over baseball like a ghost ship - monumental yet ephemeral, both inspiration and warning.

Their 116 wins remain unmatched in the modern era, a statistical impossibility in an age of enforced parity. Yet they exist more as a question than an answer: How can a team be this great and still not win?

Their legacy ripples through the game. Ichiro’s arrival reshaped MLB’s global landscape. Their collapse sparked endless debates about playoff formats and the cruel indifference of October.

And in Seattle, they became something deeper: a lost paradise.

For 21 years, the Mariners wandered. When they finally returned to the playoffs in 2022, the echoes of that team were everywhere.

Reflecting on it, Mike Cameron put it plainly: “We had an unbelievable season, but not finishing it off with a championship leaves a void.”

A perfect summer. An unfinished story. A team suspended between greatness and closure.

And isn’t that what haunts us most?

Not the clean breaks - but the suspended stories.

THE LESSON

The 2001 Mariners teach us that perfection lives in accumulation, not completion.

Their 116 wins are baseball’s version of Sisyphus - pushing the boulder higher than anyone else, only to watch it tumble just before the summit.

They remind us that sports, like life, rarely offer the neat conclusions we crave. We celebrate sustained excellence, but we remember dramatic endings.

Their greatness is etched in the record books, yet it’s the teams that win in October that live in memory.

Maybe that’s why the 2001 Mariners endure - not just as numbers, but as a feeling. A perfect summer. A broken autumn. A story left unresolved.

For Mariners fans, 116 is both triumph and tragedy - a number that will never be repeated, and never quite satisfies.

It’s baseball’s grandest reminder: the journey can be magnificent, even when the ending is not.

The Deep Dive:

📰 : A Retrospective Look at the 2001 Seattle Mariners (Beyond the Box Score)

🎥 : How the 2001 Mariners Went from 116 Wins to Historic Drought (Secret Base)

Life’s endings rarely deliver the courtesy of a curtain drop.

No dramatic goodbye. No door slammed shut. No moment when you’re told:

This is the last time you’ll be here.

This is the last time you’ll see them.

This is the last time it will feel like this.

Some endings arrive so quietly you don’t even realize they’ve come. One day, you just look up, and the thing that once defined you - the relationship, the dream, the version of yourself you swore would last forever - is already gone.

At first, that feels like the real tragedy.

You tell yourself you would’ve fought harder if you’d known. Memorized their laugh. Paid attention.

But the truth is, that’s what makes it perfect.

In Lost in Translation, Charlotte’s marriage is dissolving in real time. Not in a fight. Not in betrayal. Just in a series of small, accumulating absences.

She and her husband share the same space, but she’s alone. Their conversations skim the surface. They were once something. Now they are something else.

Then she meets Bob.

He’s older, weathered, walking his own tightrope of discontent. They’re strangers in Tokyo, orbiting the same sense of displacement. For a few brief days, they belong to each other.

But not in the way movies usually depict belonging. There’s no grand confession. No plan to stay together. No attempt to force permanence into something meant to be fleeting.

Like the Mariners’ perfect summer, Charlotte and Bob exist in a bubble of time, suspended from the normal rules. What makes their connection meaningful isn’t its longevity - it’s its intensity. The way it changes them both despite its brevity.

The whispered words we never hear at the end aren’t important.

What matters is that something passed between them - something that made them more complete, if only for a moment.

Charlotte and Bob’s connection is rare. But it isn’t unfinished.

It isn’t incomplete.

They understand - without saying it - that this only exists because it’s temporary. That’s what makes it beautiful. If they met at a different time, in a different place, under different circumstances, they wouldn’t be these versions of themselves.

The fact that it can’t last doesn’t diminish its meaning.

It creates it.

This is the paradox of impermanent perfection.

We’re taught that something is only valuable if it endures. That real success is the thing that lasts. That real love is the one that never leaves. That real happiness is something you can hold onto.

But some of the best things in life aren’t meant to be kept.

Sometimes, you lose something because you failed to notice it was slipping away.

And sometimes, you lose something because it was never meant to stay.

Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel-winning psychologist, studied how we experience time. With Barbara Fredrickson, he introduced the Peak-End Rule: we don’t remember entire experiences - we remember how they felt at their peak, and how they ended. Those two snapshots shape everything.

A great conversation with a friend that ends in awkward silence? It tints the whole memory.

A decade of brilliance that stumbles at the finish line? History often remembers the stumble.

The 2001 Mariners live inside this psychological truth. Despite months of dominance, despite records that may never fall, their story is forever colored by five brutal games against the Yankees.

The Peak-End Rule explains why 116 wins feel incomplete - why players like Mike Cameron still speak of lingering voids, even after a season most only dream of.

It’s why we struggle with impermanence.

If something beautiful doesn’t have a satisfying conclusion, was it really beautiful at all?

But what if we flipped it?

What if the impermanence is the satisfying conclusion?

What if it means it existed exactly as long as it was supposed to?

Bob and Charlotte don’t need to ruin what they had by pretending it was something else.

The Mariners don’t need a championship to prove 116 wins were extraordinary.

A love that doesn’t last forever doesn’t mean it wasn’t real.

A dream that doesn’t end the way you imagined doesn’t mean it wasn’t worth chasing.

Some things aren’t meant to last.

They’re meant to be felt.

And that is enough.

Because the things we can’t hold onto forever are precisely the ones that change us.

Permanently.

Lindsey Vonn, for a podium finish to close out her comeback season: “People said I was too old, that I wasn’t good enough anymore.” (SkiMag)

Dawson Baker, for cheering even when they can’t hear you: When you set up the celly cam at halftime and end up capturing the sweetest moment🥹 (BYU MBB / Instagram)

For Candace Parker

Before it was announced she’d be the third member of the Los Angeles Sparks to have her jersey retired.